Inspired by many other public syllabuses such as the #FergusonSyllabus, #CharlestonSyllabus, #StandingRockSyllabus, and others, I decided to create a “syllabus” (more like a generic reading list) of Anishinaabe Studies. This was, in part, an experiment I have wanted to do for a while, in response to a number of academics (including some Anishinaabe scholars!) who told me there wasn’t enough material to claim the existence of Anishinaabe Studies as a field. There are, as of August 15th 2018, over 80 different books (plus a few articles) on this list, most of them by Anishinaabe writers. This doesn’t even begin to touch the vast amounts of Anishinaabe writing that is not in the form of book-length scholarship.

This list is very much a work in progress and I welcome additions and suggestions! Many sections are particularly incomplete, like the history sections and the gender/sexuality sections. And since I’m only one person, I’m sure my biases show (there is a lot of Wisconsin/Minnesota Ojibwe material, which is just because that’s where I grew up and what I know). Please note that I have not read everything on this list and can’t vouch for all of it being perfect. I offer it anyway with the idea that most of it, hopefully, is worth engaging with. In addition, I hope to make a version of this at some point specifically focusing on non-scholarly material and things that can be accessed for free–but I am also a student about to start the school year, so that may be a ways off.

Note: I have chosen to use Anishinaabe as a catch-all umbrella for those Native people who speak a variety of the language known as Anishinaabemowin, or who are citizens of a nation that was part of the Three Fires of Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi people. Please correct me if I have mislabeled anyone’s identity. I have tried to include authors’ tribal affiliation where applicable; Anishinaabe authors are identified by their band or tribe alone in most cases.

Mino-agindaasog!

EGINDAMANG JI-GIKENIMIGOYAANG ENISHINAABEWIYAANG:

AN ANISHINAABE STUDIES SYLLABUS

Anishinaabemowin and Anishinaabe epistemologies

- Leanne Simpson (Alderville), Dancing on Our Turtle’s Back: Stories of Nishnaabeg Re-creation, Resurgence and a New Emergence

- Lawrence Gross (White Earth), Anishinaabe Ways of Knowing and Being

- GLIFWC, Dibaajimowinan: Anishinaabe Stories of Culture and Respect

- Leanne Simpson (Alderville), The Gift is in the Making: Anishinaabeg Stories

- Eds. Jill Doerfler (White Earth), Niigaanwewidam James Sinclair (St. Peter’s/Little Peguis), Heidi Kiiwetinepinesiik Stark (Turtle Mountain), Centering Anishinaabeg Studies: Understanding the World Through Stories

- Thomas D. Peacock (Fond Du Lac), Marlene Wisuri, Ojibwe Waasa Inaabidaa: We Look in All Directions

Anishinaabe law and governance

- Cary Miller (St. Croix/Leech Lake descendant), Ogimaag: Anishinaabeg Leadership, 1760-1845

- Jill Doerfler (White Earth), Those Who Belong: Identity, Family, Blood, and Citizenship Among the White Earth Anishinaabeg

- Heidi Kiiwetinepinesiik Stark (Turtle Mountain), Stealing fire, scattering ashes: Anishinaabe expressions of sovereignty, nationhood, and land tenure in treaty making with the United States and Canada, 1785—1923 (dissertation)

- John Borrows (Chippewas of Nawash), Drawing Out Law: A Spirit’s Guide

- Anton Treuer (Leech Lake), The Assassination of Hole-in-the-Day

Anishinaabe knowledge and science

- Wendy Makoons Geniusz (Cree/Métis), Our Knowledge Is Not Primitive: Decolonizing Botanical Anishinaabe Teachings

- Rheault Ishpeming’enzaabid D’arcy (Nipissing Anishinaabe descendant), Anishinaabe Mino-Bimaadiziwin (dissertation)

- Robin Wall Kimmerer (Citizen Potawatomi), Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants

- Robin Wall Kimmerer (Citizen Potawatomi) Gathering Moss: A Natural and Cultural History of Mosses

- Mary Sisiip Geniusz (Cree/Métis), Plants Have So Much to Give Us, All We Have to Do Is Ask

- Basil Johnston (Chippewas of Nawash), Honor Mother Earth

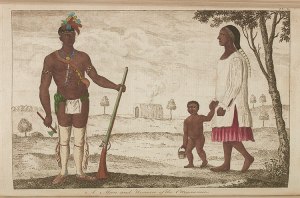

History to 1900

- Michael Witgen (Red Cliff), Infinity of Nations: How the Native New World Shaped Early North America

- Mattie Harper (Bois Forte), French Africans in Ojibwe Country: Negotiating Marriage, Identity and Race, 1780-1890 (dissertation)

- Phil Bellfy (White Earth), Three Fires Unity: The Anishnabeg of the Lake Huron Borderlands

- Donald B. Smith, Mississauga Portraits: Ojibwe Voices from Nineteenth-Century Canada

- Theodore Karamanski, Blackbird’s Song: Andrew J. Blackbird and the Odawa People

- Heidi Bokaher, Nindoodemag: Anishinaabe Identities in the Eastern Great Lakes Region, 1600 to 1900 (dissertation)

Early Anishinaabe literature

- Gerald Vizenor (White Earth), Songs in the Spring: Anishinaabe Lyric Poems and Stories

- Jane Johnston Schoolcraft (Lake Superior Ojibwe), The Sound the Stars Make Rushing Through the Sky

- Bethany Schneider, “Not for Citation: Jane Johnston Schoolcraft’s Synchronic Strategies” in ESQ: A Journal of the American Renaissance 54:1-4 (2008)

- Christine R. Cavalier, “Jane Johnston Schoolcraft’s Sentimental Lessons: Native Literary Collaboration and Resistance in MELUS 38:1

- William Warren (Lake Superior Ojibwe), A History of the Ojibway People

- Andrew Blackbird (L’Arbre Croche Odawa), History of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of Michigan

- Simon Pokagon (Pokagon Potawatomi), The Red Man’s Rebuke and other publications

American and Canadian colonization

- Ignatia Broker (White Earth), Night Flying Woman: An Ojibway Narrative

- John P. Bowes, Land Too Good for Indians: Northern Indian Removal

- Basil Johnston (Chippewas of Nawash), Indian School Days

- Brenda Child (Red Lake), Boarding School Seasons: American Indian Families, 1900-1940

- Winona LaDuke (White Earth), The Militarization of Indian Country

- Erik Redix (Lac Courte Oreilles), The Murder of Joe White: Ojibwe Leadership and Colonialism in Wisconsin

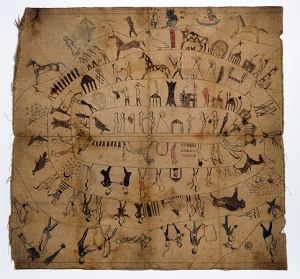

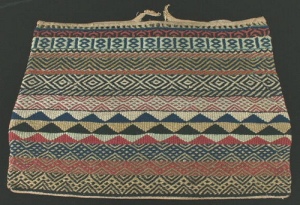

Anishinaabe art

- David Penney, Gerald McMaster (Plains Cree/Siksika), Before and After the Horizon: Anishinaabe Artists of the Great Lakes

- Carmen L. Robertson (Lakota), Mythologizing Norval Morrisseau: Art and the Colonial Narrative in the Canadian Media

- Daphne Odjig (Wiikwemkoong), Odjig: The Art of Daphne Odjig, 1960-2000

- Gertrude Prokosch Kurath, Fred Ettawageshik (Little Traverse Bay Band), Jane Ettawageshik (Little Traverse Bay Band), The Art of Tradition: Sacred Music, Dance, & Myth of Michigan’s Anishinaabe, 1946-1955

- Michael D. McNally, Ojibwe Singers: Hymns, Grief, and a Native Culture in Motion

- Kirsten Buick, Child of the Fire: Mary Edmonia Lewis and the Problem of Art History’s Black and Indian Subject

Gender and sexuality

- Brenda Child (Red Lake), Holding Our World Together: Ojibwe Women and the Survival of the Community

- Robert Innes (Cowessess), Kim Anderson (Métis), Indigenous Men and Masculinities

- Lisa Poupart (Lac Du Flambeau), “Ojibwe Women of the Great Lakes” in Women’s Rights: A Global View

- Kim Anderson (Métis), Life Stages of Native Women: Memory, Teachings, and Story Medicine

Modern Anishinaabe literature

(Waaaaay too many to list exhaustively. Some suggestions to get you started…)

- Fiction: Louise Erdrich (Turtle Mountain), Gerald Vizenor (White Earth), Leanne Simpson (Alderville), Carole laFavor (Ojibwe), Lois Beardslee (Anishinaabe/Lacandon), Ruby Slipperjack (Whitewater Lake), Drew Hayden Taylor (Curve Lake), David Treuer (Leech Lake), E. Donald Two-Rivers (Seine River)

- Poetry: Louise Erdrich (Turtle Mountain), Heid Erdrich (Turtle Mountain), Gerald Vizenor (White Earth), Leanne Simpson (Alderville), Kateri Akiwenzie-Damm (Chippewas of Nawash), Gwen Benaway (Métis/Anishinaabe), Margaret Noodin (Ojibwe), Leslie Belleau (Garden River), Lenore Keeshig Tobias (Chippewas of Nawash), Mark Turcotte (Turtle Mountain), Kimberly Blaeser (White Earth), E. Donald Two-Rivers (Seine River)

- Nitaawichige: Selected Poetry and Prose by Four Anishinaabe Writers

- Stories Migrating Home: A Collection of Anishinaabe Prose

- Traces in Blood, Bone, And Stone: Contemporary Ojibwe Poetry

20th and 21st century history

- Rosalyn LaPier (Blackfeet/Métis), David Beck, City Indians: Native American Activism in Chicago, 1893-1934

- John Low (Pokagon Potawatomi), Imprints: The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians and the City of Chicago

- Larry Nesper, The Walleye War: The Struggle for Ojibwe Spearfishing and Treaty Rights

- Julie L. Davis, Survival Schools: The American Indian Movement and Community Education in the Twin Cities

- Chelsea Vowel (Métis), Indigenous Writes: A Guide to First Nations, Métis & Inuit Issues in Canada

- Tanya Talaga (Fort William descendant), Seven Fallen Feathers: Racism, Death, and Hard Truths in a Northern City

- Eds. Nigaanwewidam James Sinclair (St. Peter’s/Little Peguis) and Warren Cariou (Métis), Manitowapow: Aboriginal Writings from the Land of Water

- David Treuer (Leech Lake), Rez Life

- Brenda Child (Red Lake), My Grandfather’s Knocking Sticks: Ojibwe Family Life and Labor on the Reservation

- Brian D. McInnes, Sounding Thunder: The Stories of Francis Pegahmagabow

Decolonization/Biskaabiiyang

- Christopher Wetzel, Gathering the Potawatomi Nation: Revitalization and Identity

- Maureen Matthews, Naamiwan’s Drum: The Story of a Contested Repatriation of Anishinaabe Artefacts

- Leanne Betasamosake Simpson (Alderville), As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance

- Winona LaDuke (White Earth), Recovering the Sacred: the Power of Naming and Claiming

- Winona LaDuke (White Earth), All Our Relations: Native Struggles for Land and Life