Tags

Lead mining and the lead rush of the 1820s is a huge part of the cultural narrative of white settlement in southeastern Wisconsin and the nearby parts of Minnesota, Illinois, and Iowa known as the Driftless Area. It’s the quintessential frontier story: white American men discover a mineral resource and flood the area, doing the manly work of mining while they slowly civilize the area for further settlement.

But the idea that there was this untapped mineral waiting to be found by Americans is almost entirely wrong. For nearly a century before that, the lead mines had been worked with increasing intensity–and not just by Indians, but by Indian women specifically.

Indigenous people had been mining for lead in small quantities for thousands of years, but it was the arrival of the fur trade and especially the firearms it brought that sparked more heavy mining by Ho-Chunk, Sauk, and Meskwaki people–an American trader predicted that in the summer of 1826 the Meskwaki would raise between 600,000 and 800,000 pounds of lead at one of their key mining sites. Having learned to smelt from early fur traders, they used the mines to make lead balls for their guns. This had two benefits: it provided an alternative trade good to furs (which could vary greatly in number and quality depending on the year), and it lessened their need to purchase musketballs from the traders.

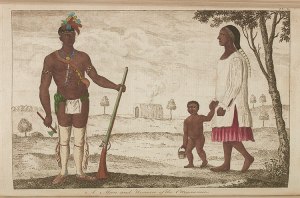

This process was highly gendered. The actual creation of ammunition was primarily men’s work, but mining itself was overwhelmingly dominated by women, with only a few elderly men participating. Indigenous women in this area were considered to have domain over the farming fields and the sugar bushes, and the mines may have been an extension of this. Like sugar-making, mining was probably a seasonal activity incorporated into the cyclical yearly activities. Women would dig square holes and dredge up the rock and ore, then broke up the deposits by heating them and dousing them with cold water before smelting the lead in furnaces cut into hillsides.

Evidence suggests that indigenous women may have had very strong proprietary feelings about the mines. As Creole communities of mostly French Canadian and mixed-blood people sprang up in the Driftless Area (such as in Prairie du Chien), only men who married Native women were permitted to even see the lead mines. One man, Julien Dubuque, was unusually granted permission to work the mines after marrying a Meskwaki woman, whose name has unfortunately been lost in the records. The work of Monsieur and Madame Dubuque expanded the mining operations by encouraging a developing Creole community that bought Indian lead in exchange for trade goods. According to Ho-Chunk sources, indigenous miners also sold musketballs to other tribes outside the region.

After the War of 1812, the American military established a more permanent presence in the region. At first, immigrating American men had to follow tradition and marry indigenous women to get involved with mining. But by the late 1820s thousands of white miners and a smaller number of black miners (both free and enslaved) had rushed to the area. The two groups of miners rarely mixed, clashing over gender roles, language, and prejudice. Worse, white men engaged in rowdy behavior, and indigenous women, who had occupied crucial positions in society until now, were abused so frequently that Indian men began to try to police them. In Prairie du Chien, the predominately metis society passed a law prohibiting “white persons skulking” around after dark.

The white miners’ abuse of Indian women, their destruction of indigenous food sources, and their relentless incursions into Indian territory were major issues for indigenous communities by 1830. Meanwhile, changing circumstances meant that women’s production of lead and maple sugar were now more central to indigenous economies than the fur trade, leaving men idle and susceptible to drunkenness and belligerence. These strains, along with longstanding conflicts over certain treaties, contributed to the outbreak of the Black Hawk War in the 1830s.

The war tore apart Indian communities and increased white fear and hatred for Indians, resulting in the policies of removal that were attempted in the next few decades. The Sauk and Meskwaki were removed several times to Iowa, Kansas, and Oklahoma. Some remained hidden in Iowa until they were allowed to purchase their own land in 1851, which they still own today as the Meskwaki Settlement. The Ho-Chunk were also removed repeatedly, to Minnesota, South Dakota, and Nebraska. Though some still live on the Nebraska reservation today, many Ho-Chunk people refused to leave their Wisconsin homeland, even walking back all the way from Nebraska. Today they have begun to reacquire their land in southeastern Wisconsin.

For more detailed information on this subject, see Economy, Race, and Gender along the Fox-Wisconsin and Rock Riveways, 1737-1832 by Lucy Eldersveld Murphy.

Reblogged this on Museu AfroDigital- Estação Portugal.

This is fascinating! Mining as an extension of farming! I wonder how many other cultures went the same route. And I wonder what could have happened if the Great Lakes lead mines had been allowed to develop industrially.

By what process did they mine the lead, exactly?

I’m not super knowledgeable about mining, but according to sources quoted in Eldersveld, they would dig square holes with one side on an angle, and then dredge up the rock and ore up that side. To break up the mineral they heated it and then dashed water over it, and then smelt the ore with the hillside forges. That’s as far as I understand, anyway!

lol

hi

I soon