I saw a post of a Hopewell pipe a few days ago and it got me thinking about Hopewell. For the unfamiliar, Hopewell is the name for the general cultural tradition and exchange network that spread across the eastern woodlands from about 200 BC to 500 AD. It’s an archaeological culture, not a linguistic or ethnic one, meaning the defining characteristics are similar types of pottery, pipes, sculpture, jewelry, and most notably, mounds. Here is a map of the various permutations of Hopewell:

Ohio Hopewell is generally considered the heart of the Hopewell exchange network, but obviously you can see Hopewellian style things appeared throughout the east. Hopewell is most famous for the large earthen mounds, created in animal shapes and swirly designs and also plain conical burial mounds, as well as the extremely beautiful pipes carved in the shape of animals and people.

I’ve spent a lot of time in the past few years learning about Cahokia and Mississippian history, and I recently got a book called Hawk, Hero, and Open Hand that was about ancient art of the eastern woodlands, in which there were a few articles about Hopewell. And looking at them, I noticed that fascinatingly the designs seemed rather familiar to me. In Mississippian art, there are certain things that are culturally familiar to me, like the duality of the sky beings and the underwater beings, but it’s a fairly mild connection with only a few elements, familiar but still not something I instinctively understand. Most people agree that the direct cultural descendants of the Mississippian tradition are Muskogean, Caddoan, and Siouan speaking people: Choctaw, Chickasaw, Maskoke, Osage, Pawnee, Wichita, Oto, Iowa, Ho-Chunk, Dakota. I was raised with Great Lakes Anishinaabe-Metis traditions, and while I have some Dakota ancestors and my ancestors were on the edges of the Mississippian/Oneota, I wasn’t raised with Dakota or Ho-Chunk or Choctaw stories and ceremonies. People who were raised with them look at Mississippian art with much more recognition, because their cultures retain elements from that, passed down for a thousand years.

But with Hopewell art, I saw some of that familiarity and it surprised me. Even on just an aesthetic level, Hopewell art seems more familiar to me than Mississippian; Mississippian art reminds me of the stark Plains painting traditions, while the curlicue lines of Hopewell look a lot like the Anishinaabe paintings I’ve seen on rocks and birchbark and canvas in modern Woodland Medicine Style art. So I started to look into Hopewell some more, curious about the connections. Like I pointed out above, there’s fairly broad agreement about who the descendants of the Mississippians are, and there’s happily increasing efforts to involve them with their own history rather than archaeologists keeping it for themselves. But Mississippian cultures continued in a recognizable form until contact with Europeans, meaning that written sources could help identify ethnic affiliations. The Hopewell peoples stopped building Hopewell-style mounds about five hundred years before the Mississippians got started, and as a result not too many people have really even tried getting into the issue of their linguistic or cultural affiliation.

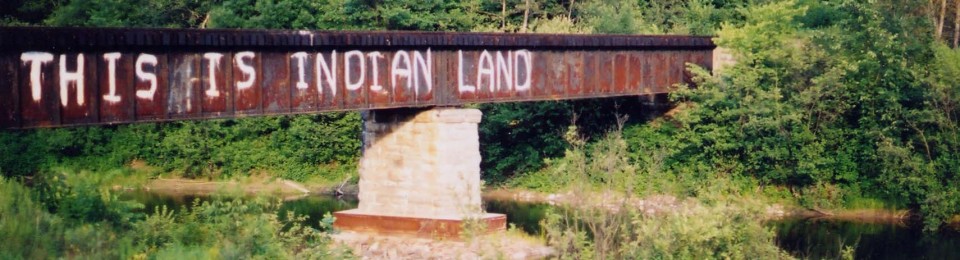

I happen to think that this is in large part because archaeologists have still failed in bringing the information they’ve gathered to indigenous people and having them direct the course of research; if my untrained Great Lakes Metis eyes can see similarities, then if you get elders looking at this stuff there is so much potential for understanding. And I do think some people have been working on this, which is good.

Anyway, from the scarce resource I could find speculating on this, the predominant opinion is that Hopewell doesn’t correspond to a single ethnic or linguistic group, but rather was a tradition shared across many. Which is sort of obvious given the history and culture of the woodlands people. The general thought is that Ohio Hopewell built off of the earlier local Adena culture, and then increased trade with other areas spread many art styles, rituals, and ideas around the area east of the Rocky Mountains. The more western types of Hopewell were probably made by Siouan speaking people, likely the ancestors of the Mississippians, who for their part built on certain Hopewell traditions. The Point Peninsula and Laurel complexes have been associated with Algonquian speakers, Laurel in particular being associated with Cree people. At least one person has suggested based on archaeology, linguistics, and oral history that the Hopewell interaction may have been associated with the spread of Algonquian people from the Proto-Algonquian homeland in southern Ontario, which I find fairly compelling. Other Hopewellians, perhaps even the Ohio Hopewellians themselves, were most likely Iroquoian-speakers.

Though I haven’t done a ton of research yet, much of this rings true for me in an instinctual way. It made me think of thee books I’ve read recently, one about Dakota history, one Wendat, and one Anishinaabe, each by indigenous people from their respective nation. In all three, there was a story of a flood caused by the underwater beings in which a muskrat dove deep into the ocean and pulled up soil which was formed into the earth on the back of a turtle. It’s the same story that I have heard from Metis, Anishinaabe, and Cree people all my life, and I was amazed at how similar all of our traditions were for three different cultures from three entirely different linguistic groups. I’ve heard it remarked by scholars that nearly all indigenous people east of the Rockies share certain basic understandings of the world, and I’d noticed that I’ve always found it easiest to understand people from that area, regardless of whether they were from the plains or the lakes or the east coast, but learning more about Hopewell has given me a very intriguing historical perspective on that. These things that we share, they were most likely also shared by Hopewell peoples, with their huge exchange influence getting farflung nations to interact and share ideas and ceremonies.

If that is the case, then Hopewell is a huge part of the shared cultural heritage of the entire eastern 3/4s of North America. And (as I continually argue) it needs to be returned to the hands and hearts of those people. For me, this entry into the world of Hopewell has been a real reality check for me because of the emotional, visceral reaction I have to it, unlike other areas ancient American history which I’m not a descendant of. It made me think, for instance, about the pipes that are some of the most famous Hopewell “artifacts.” Pipes are an extremely sacred part of modern traditional culture for most people in the eastern woodlands, and they’re things that must be treated very carefully. One elder (I forget what tribe he’s from, but one that is connected to Hopewell and Mississippians) commented that as he got to know the pipes better, he began to wonder if it was appropriate for them to be displayed. And he said he was still conflicted, because certainly there is the way our ancestors would have done it (if they buried it, it was intended to stay buried), but there is also to consider the fact that these things are incredibly precious in teaching our youth about our history, and the fact that time passes and things change, and we are no longer in Hopewell times. I personally am still struggling with the question of how I feel about displaying images of the pipes, which is why none appear here.

It’s an extremely touchy thing. If indigenous people lay claim to the bones and art of ancestors like the Hopewell, there’s even more opportunity for clashing with archaeologists than already exists, and that will be a difficult thing to navigate. In addition, there’s also the difficulty that due to the long amount of time that has passed, no individual tribe can lay sole claim to Hopewell, and that has the potential to create conflict between and within tribes who disagree about what to do with the pieces of history. Still, I think all of these things are worth dealing with for the benefits that will come from returning Hopewell history to the hands of indigenous people whose ancestors made it. Learning this, about the influential history that my direct cultural ancestors were involved with, has been really amazing, and that is something I want other indigenous people to be able to share.